Designing for Machinability: How to Optimize Part Geometry for CNC Production

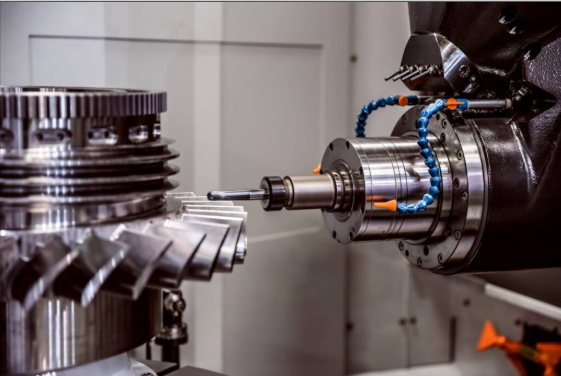

CNC machining has transformed modern manufacturing by enabling the precise and repeatable production of components across industries like aerospace, automotive, medical devices, and consumer electronics. However, the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of CNC processes are heavily influenced by part geometry. Engineers and designers must consider not just function but also how a part machine will interact with tools, fixtures, and materials. Designing for machinability ensures parts can be produced with fewer complications, faster turnaround, and lower costs without compromising quality.

Understanding Machinability in CNC Production

Machinability refers to how easily a material or design can be shaped, cut, or finished using machining processes. While machinability is often associated with material properties such as hardness or ductility, design geometry is equally important. Features like deep cavities, thin walls, or extremely tight tolerances can make machining challenging, even with advanced CNC equipment. By tailoring part geometry with machinability in mind, designers minimize tool wear, reduce setup times, and prevent costly production delays.

Simplify Part Geometry Whenever Possible

Complex designs are often necessary, but unnecessary complexity should be avoided. Each additional contour, groove, or undercut increases programming time and machining operations. For example, parts with intricate internal features may require specialized tools or multiple setups. Simplifying the geometry allows for faster machining and reduces the risk of tool deflection. In practice, a simpler design may also improve reliability since fewer features mean fewer stress concentration points where failures could occur.

Optimize Wall Thickness and Feature Size

Thin walls and delicate features are difficult to machine because they vibrate under cutting forces and may deform. A general rule of thumb is to maintain a minimum wall thickness of at least 1 mm for metals and 1.5 mm for plastics. Similarly, features like ribs or pockets should not be too deep relative to their width, as this makes chip evacuation and tool access more difficult. Maintaining proportional dimensions allows cutting tools to operate efficiently and extends tool life.

Standardize Hole Sizes and Depths

Holes are among the most common features in CNC machined parts, but not all holes are created equal from a machinability perspective. Designers should use standard drill sizes whenever possible, as custom diameters require end mills or boring tools that add complexity. Additionally, hole depth should be limited to no more than four times the hole diameter unless absolutely necessary. This guideline helps maintain accuracy and prevents tool breakage.

Avoid Sharp Internal Corners

Milling tools are cylindrical, which means creating perfectly sharp internal corners is impossible without secondary operations like electrical discharge machining (EDM). Instead, designers should specify fillets or radii in internal corners. Not only does this align with tool geometry, but it also reduces stress concentrations, improving the mechanical strength of the part. As a rule, corner radii should match or exceed the tool radius being used.

Consider Tool Accessibility and Approach Angles

In CNC machining, tools must physically reach every surface of a part. Designs with undercuts, hidden features, or steep internal walls often require specialized tooling or multi-axis setups. While 5-axis CNC machines can handle complex geometries, they increase machining time and cost. A machinability-focused design ensures that most features are accessible from standard 3-axis operations, keeping production more economical.

Balance Tolerances with Functionality

Tolerances are critical for ensuring parts fit and function properly, but unnecessarily tight tolerances drive up costs. For instance, specifying ±0.01 mm across an entire part may require additional finishing passes or specialized equipment. Instead, designers should apply tight tolerances only to critical features like bearing fits, sealing surfaces, or alignment points. Non-critical areas can often accept looser tolerances without affecting performance.

Account for Material Properties

Different materials respond to machining in unique ways. Aluminum alloys, for example, are highly machinable due to their softness and excellent chip evacuation. Stainless steel, on the other hand, is prone to work hardening and requires slower speeds and tougher tools. When optimizing part geometry, designers should consider how the chosen material interacts with machining forces. Choosing machinable alloys or adjusting geometry to reduce tool load can significantly improve production outcomes.

Design for Fixturing and Workholding

A well-designed part not only accounts for machining but also for how it will be held during machining. Parts with irregular shapes or minimal flat surfaces are difficult to fixture securely, leading to vibration and inaccuracies. Designers should incorporate features like flat surfaces or clamping zones that make fixturing straightforward. This is especially important for production runs where efficiency and repeatability are paramount.

The Role of CAD/CAM in Optimizing Geometry

Modern computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) software help bridge the gap between design intent and machinability. Designers can simulate toolpaths, check for collisions, and validate part accessibility before production begins. By using CAD/CAM tools early in the design process, potential machining issues can be resolved proactively, saving time and cost.

Conclusion

Designing for machinability is a crucial aspect of modern CNC production. By optimizing part geometry—simplifying designs, standardizing features, applying appropriate tolerances, and considering tool accessibility—engineers can ensure that parts are efficient to manufacture without compromising function. Taking machinability into account leads to better use of resources, reduced production costs, and longer tool life. For industries that rely on both mechanical precision and electronic performance, this mindset applies across the board, whether producing structural components or integrating advanced technologies like the eagle 1000 fsc motherboard. Ultimately, understanding the relationship between design and machining helps manufacturers produce high-quality, reliable components that meet the demands of today’s industries.